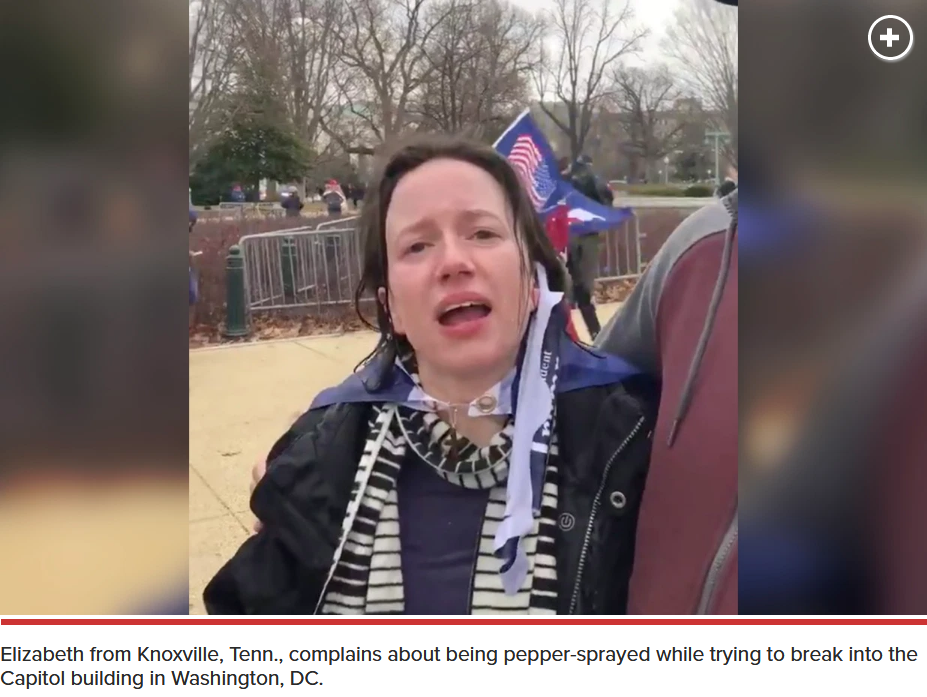

Interviewer: Ma’am, what happened to you?

Rioter from Knoxville: I got maced [wipes away tears, breathlessly]

Interviewer: You got maced. And what happened? You were trying to go inside the Capitol?

Rioter from Knoxville: [Indignantly] Yeah! I made it like a foot inside and they pushed me out and the maced me!

Interviewer: What is your name and where are you from?

Rioter from Knoxville: My name is Elizabeth; I’m from Knoxville, Tennessee!

Interviewer: And why did you want to go in?

Rioter from Knoxville: We’re storming the Capitol! It’s a revolution!

_______________

Attendees of Trump’s rally-turned-riot stormed the Capitol at the direction of the president. They attempted to stop Congressional certification of Joe Biden’s electoral win and the peaceful transition of power that has defined American government for centuries. But many rioters seemed unprepared considering the scale of their ambitions. The apparent surprise of the rioter from Knoxville at law enforcement’s response suggests many involved were animated by visions of revolution different from that of their flak-jacketed comrades. For rioters like Elizabeth, January 6th was a genteel, candy-coated revolution, closer to carnival than coup. She and others were Revolution Tourists.

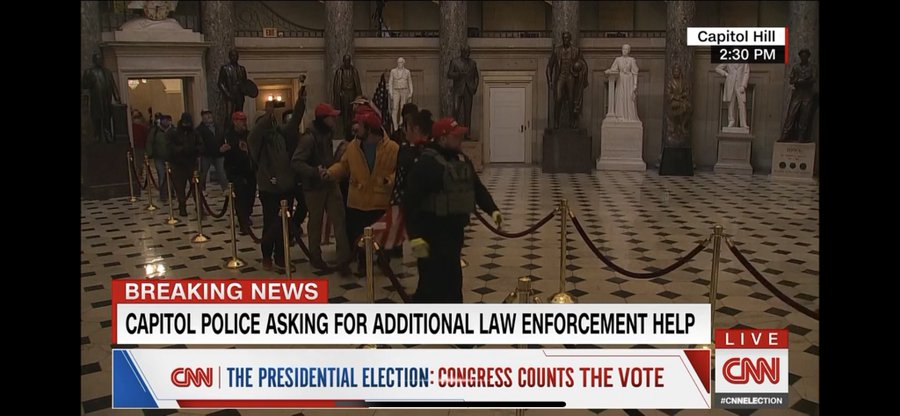

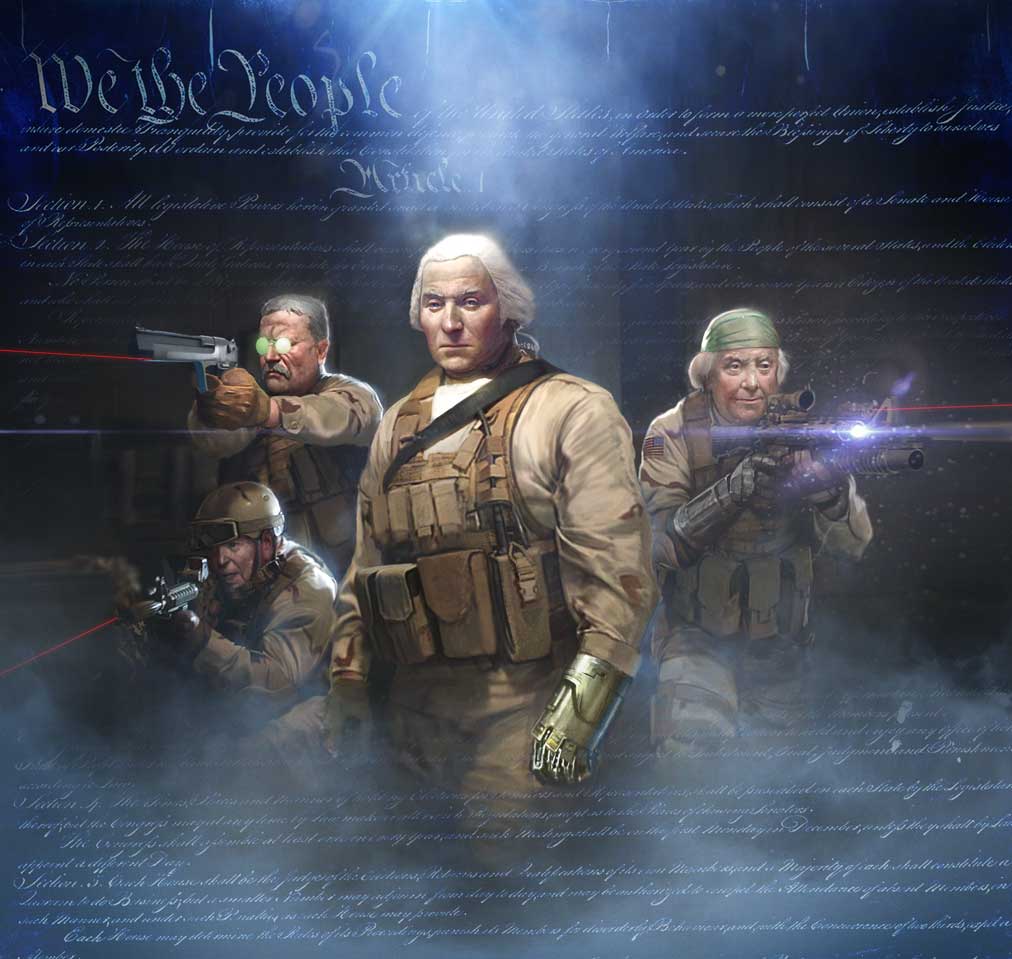

To be sure, many Capitol rioters were prepared for violence. Video footage shows the Capitol steps packed with men “kitted up” in tactical gear. They came in flak jackets, clutched zip-tie hand restraints and assault fashion reminiscent of Call of Duty. White men between 18 and 50 can be seen kicking doors down, busting windows and beating a fallen Capitol police officer because they believe conspiracies of election fraud promoted by Republican political leaders and far-right media.

Others storming the building, by contrast, seemed more prepared for festivities than ferocity. Live scenes at the Capitol had a jamboree atmosphere of Revolution Tourism. Amused and casually dressed middle-aged men took selfies with fellow rioters and Capitol officers. In plumes of tear gas, a well-dressed woman carefully lifts her stylish purse through a shattered window frame. A group of twenty-somethings scurried up and down climbing ropes like outdoor enthusiasts on a sporty weekend getaway. Once inside the building, many who had forcibly entered the broken doors of the building then formed orderly lines as they meandered through Statuary Hall within the velvet roped walkway.

These Tourist Revolutionaries were not dressed for violent insurrection. Nor were they happy patriots there to admire institutions of democracy, as Republican apologists have suggested. They were dressed for a Trump rally, and it is not clear that these festival-goers fully understood the gravity of their choices on that day. This does not make them less culpable. It does, however, make their actions more frightening. Elizabeth from Knoxville’s view of revolution speaks to the privilege and ignorance underlying the danger of a shallow and mythical version of the American Revolution and American politics in general.

Elizabeth became a meme after complaining to a reporter that she was maced when trying to break into the Capitol complex. The preposterousness of a “revolutionary” expressing indignation after being repulsed triggered the usual mockery online. Georgia Aspinall at Grazia has cautioned against such mockery. “The sheer delusion of this woman, so bold in her conviction that this was necessary, so confused and upset that police stopped her from attacking the US democracy . . . is terrifying.”

Aspinall is right. Beneath the easily mocked sense of entitlement is a deeply confused sense of American history and politics. Yes, the premise of election fraud that animated these crowds in the first place was a lie. The more pressing issue Aspinall sees is how Elizabeth from Knoxville was unable to recognize the difference between democratic and anti-democratic political action.

What should we make of the throngs who were not participating in a sort of serious-minded coup attempt like their flak-jacketed comrades? The insurrectionists in piano scarves and colorful tailgate facepaint suggest that these tourist revolutionaries saw the trip to DC (from New Jersey, Knoxville, Arkansas) as a symbolic performance of American independence and a rejection of elites cartoonishly painted for them by reckless political rhetoric and a post-Truth media ecosystem that greedily amplifies that which inflames.

The misunderstanding of American history that animated rioters is at the root of the conflict. Tourist Revolutionaries, energized by the symbolism of “1776,” confuse the tyranny of the monarch King George with the compromises of democracy and shared self-governance with fellow Americans. The carnival sense of patriotic revolt allowed rioters to happily pose for photos in the act of theft without a sense of the criminality of stealing. The carnival version of 1776 paints revolution as revelry and confuses protest with sedition.

If Elizabeth from Knoxville’s shock is genuine, it suggests that many of the rioters cannot understand that they have broken laws. In their minds, they should have the privilege to trespass because the Capitol is public property, their property. Elizabeth may have wondered how patriots could be on the wrong side of the law.

Rioters like Elizabeth have a mythical and sanitized understanding of American history, one that has lost the gritty and horrifying elements of revolution. The amputated limbs. The slumped bodies after British soldiers fired into an angry Boston crowd. The newspaper editors who were jailed for insulting colonial governors. The tyranny of princely rule without representation. These dirty and gangrenous parts of the American Revolution are missing from Elizabeth’s version of American history. As a tourist, Elizabeth understood threatening lawmakers as an extension of patriotic citizenship.

Tourist Revolutionaries on display during the Trump riot were engaging in a symbolic act that reenacts a mythical history of the country. Like visitors to a Renaissance fair or audiences at Medieval Times Dinner Theater, they did not expect authorities to respond to illegal occupation of Federal buildings with force. Her indignation speaks volumes about how symbols of political rhetoric can obscure the very real danger of “doing revolution.” Being met with force is surprising to those participating in Tourism Revolution. They complain of injury as if slapped by Goofy at Disneyland.

This was a symbolic act for a substantial number of Trump supporters who were misled by President Trump to believe they were fighting for the preservation of America rather than the subversion of electoral democracy to prop up the president’s personal ambitions.

Tourist Revolution performs a celebratory but incomplete understanding of American history, one all Americans share at Fourth of July parties and fireworks displays standing in for the red glare of actual warfare. The symbolic rhetoric that brought Elizabeth and others to the nation’s capital became literal, but it is not clear that many rioters understood the difference. This should come as no surprise in a political-media system unable to sort myth and symbol from reality for citizens. As these symbols slip from protest speech to seditious action, we can see that our fractured media is not just a quirk of social media. It is a threat to democratic governance more menacing than any pitchfork or pipebomb.