New administrations bring with them a new philosophy of governance. This is true of media governance as well. The pendulum swing from Democratic to Republican control of the presidency is, at times, a significant shift in media governance. Executive orders, proposed legislation, new commission leadership, and new telecommunications priorities all follow.

Here, we will watch some of these changes introduced by Trump’s second term. Tracking the shift in media governance is particularly important with this new administration.

Why? A couple of reasons. First, Trump has had great success challenging the mainstream press, particularly when outlets like CNN or the New York Times repeat elite, institutionalist criticism of Trump. He has made a meal of labeling criticism as “fake news.” The attack resonates with a skeptical American public that has historically low trust in TV news.

Second, these attacks resonate with an American public that has historically low trust in TV news. The Trump campaign’s rhetorical skewering of “mainstream media” resonates with his core voter base. Hundreds of thousands of his supporters feel aggrieved. They do not trust the American media system, and, when Trump supporters appear in outlets like CNN, they often experience condescension rather than representation. As a result, basic functions of the press like reflecting public will and fact-checking government have been crippled. A democratic media system cannot function without public legitimacy.

This dynamic between the politician and his supporters means we can anticipate some radical proposals in FCC actions, how content regulation evolves, and how private media companies cover politics.

Will broadcast licenses be challenged for how private news companies reported on the White House? How will coverage of immigration debates adapt to a new legal environment of threats from the FCC? Will the billionaire owners of social media companies fall further in line with Trump’s directives in response to the content moderation requests from the Biden administration? How will Trump’s FCC and Department of Justice use existing law to reshape the American news system?

We will attempt to chart some of these changes in order to better understand how media policy serves the presidency and what kind of social goals Trump 2.0 appears to pursue with policy and law. This record will be an ongoing and periodically updated.

Trump 2.0: Executive Orders and FCC Media Bias Investigations

Right out of the gate, Trump’s team has set out an agenda with the release of an Executive Order and a change in FCC leadership. Let’s examine recent FCC decisions before turning to the White House EO.

Brenden Carr, a first-term Trump appointee and telecommunications lawyer, has taken leadership of the FCC. Telecomm wonks like Carr are not known for partisan statements. In fact, telecomm policies are rarely framed as a right-left debate in public. No surprise then that Biden renominated Carr in 2023 despite Carr being a Trump appointee and harsh critic of Biden’s presidency.

Carr, however, seems to break from this non-partisan tradition. In a 2020 interview, Carr said, “[s]ince the 2016 election, the far left has hopped from hoax to hoax to hoax to explain how it lost to President Trump at the ballot box.”

Carr is not just shooting off rhetoric. Less than a week into his new role as head of the commission, he has started “bais investigations” into CBS, NBC, ABC. NPR and PBS are also under the gun for, ostensibly, accepting sponsorship support while also receiving federal funding. The underlying motive is more likely to starve media that remain shielded from executive coercion and quiet independent voices that might undermine government control of political narratives.

Carr’s legal moves do not seem in-line with Trump’s Executive Order of January 20, 2024. Section 2 of the Executive Order states:

Sec. 2. Policy. It is the policy of the United States to: (a) secure the right of the American people to engage in constitutionally protected speech; (b) ensure that no Federal Government officer, employee, or agent engages in or facilitates any conduct that would unconstitutionally abridge the free speech of any American citizen; (c) ensure that no taxpayer resources are used to engage in or facilitate any conduct that would unconstitutionally abridge the free speech of any American citizen; . . .

The executive order is a case study in why policy pronouncements fail when they are muddied by partisan rhetoric. And let’s be clear that is what is happening. The order mirrors the aggressive campaign style but accomplishes little in terms of media law and policy due to self-contradiction.

As policy, the EO falls apart In the larger context of executive branch actions. Specifically, FCC Chairman Carr’s investigation of American news outlets appears to violate the spirit of Section 2. Section 3(a) states “[n]o Federal department, agency, entity, officer, employee, or agent may act or use any Federal resources in a manner contrary to section 2 of this order” (EO, Jan 20, 2025).

Carr’s FCC has done precisely what Trump’s Order appears to prohibit.

What policy documents do

Policy documents help industry leaders craft business plans. Partisan pronouncements, by contrast, are less helpful. They aim to undermine competitors for power rather than spell out the administration’s approach to media governance. Those watching the administration’s early moves to better anticipate regulatory conditions will have to wait.

Inconsistent policy is a sign of poor coordination among leadership at the White House Office. It is also a sign of incoherent principles guiding the new administration.

the basics: free speech law and tolerating political speech

Historically, media content regulations have been viewed as anti-American. Aside from the usual prohibitions against indecency (think: wardrobe malfunctions) and incitement, it has been mostly unthinkable to formally investigate news outlets for having political leanings. The behemoth partisan presence of Fox News in American politics under Democratic administrations is an obvious example. Fox’s “fair and balanced” news underscores the tolerance for criticism entailed by free expression law. The Biden, Obama, and Clinton administrations all begrudgingly accepted antagonism of Fox News personalities. These administrations embraced fair and unfair criticism as part of the job.

Why? Because prosecuting or regulating private media companies for perceived political bias is not just unthinkable. It is unconstitutional. The First Amendment prohibits Congress from “abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press.” These administrations understood diversity of opinion was more valuable to American government than silencing political speech. The president needed to answer critics.1

Free expression is a cornerstone or American media law and culture. The Trump administration has sent up some confusing signals about actual media policy that will define Trump’s second term. One early Executive Order claims to “end federal censorship” of the Biden administration . . . even as Trump’s FCC appears to be attempting to quiet the speech of major news outlets like CBS and NPR.

We will continue to watch media policies of Trump 2.0 as they take shape over the next four years. Free expression has a long tradition in the United States. However, free expression traditions are not guaranteed to remain unchanged in this political climate. Both the White House and a growing number of Americans are doubtful of American media and the legal environment that allows vigorous debate and criticism of government. Tracking policy changes will at least give us a glimpse into the new directions in store for the American public sphere. Stay tuned!

1 The First Amendment’s speech clause has expanded throughout the American system to include state legislatures, even including public universities which are disallowed from punishing students for social media posts since they are government institutions.

2 The presidency is no exception to First Amendment prohibitions, though it is worth noting the Supreme Court never ruled on John Adams’s Alien and Sedition Act, a censorship and deportation law of the early republic period that reflects the Trump administration’s agenda.

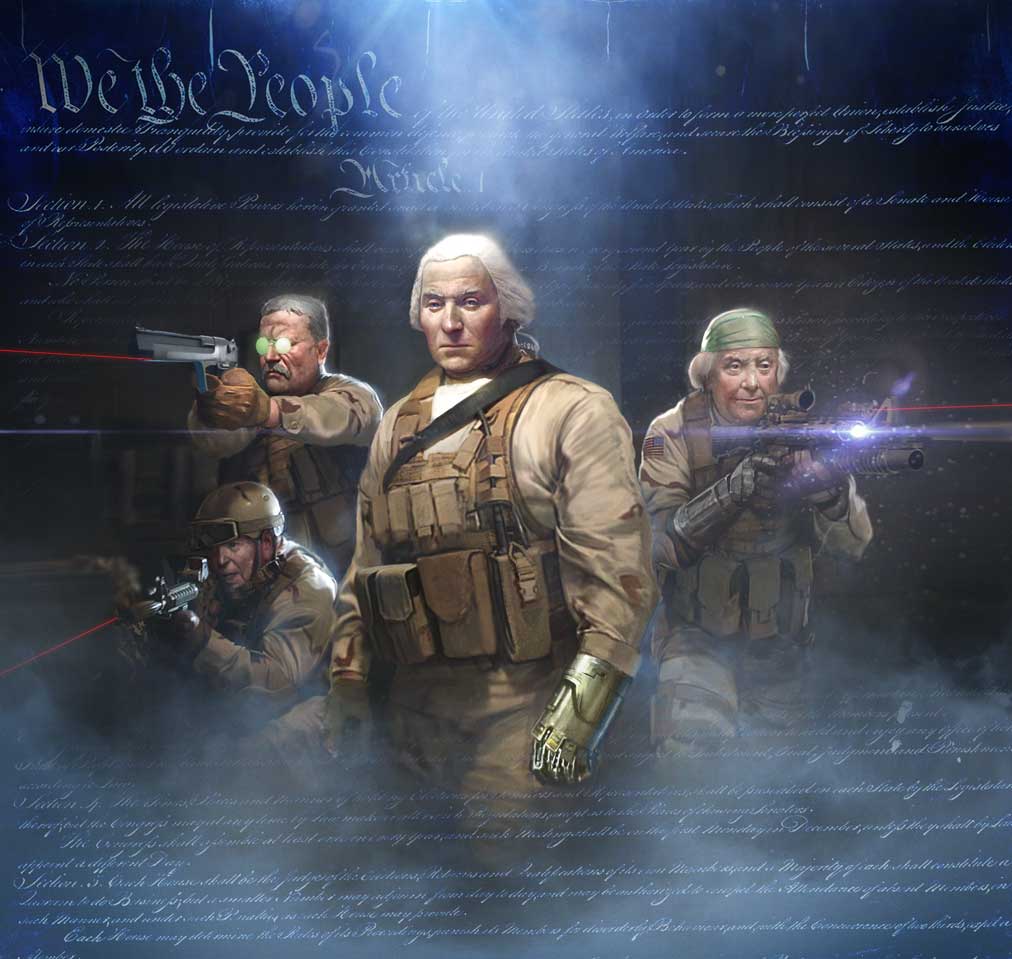

Sharable partisan content, regardless of its support for right or left, Democrat or Republican, left vs. far left, is best understood as an outgrowth of the information bubbles and fragmentation of the American electorate. Disrupt media, in Dugin’s model, fortifies group identity. In line with the Council of Europe’s 2017 report, we reframe this strategy of “information pollution” as a question of culture and ritual rather than simple information transmission, recognizing that “communication plays a fundamental role in representing shared beliefs” (7). RT’s campaign found success by taking advantage of the commercial foundations of the US (new) media system and forms of redistribution enabled by user sharing functions of new media platforms.

Sharable partisan content, regardless of its support for right or left, Democrat or Republican, left vs. far left, is best understood as an outgrowth of the information bubbles and fragmentation of the American electorate. Disrupt media, in Dugin’s model, fortifies group identity. In line with the Council of Europe’s 2017 report, we reframe this strategy of “information pollution” as a question of culture and ritual rather than simple information transmission, recognizing that “communication plays a fundamental role in representing shared beliefs” (7). RT’s campaign found success by taking advantage of the commercial foundations of the US (new) media system and forms of redistribution enabled by user sharing functions of new media platforms.