Category: Media Politics

A Quit Facebook Movement? Some Academic Research

Here is a selection of public discourse related to these questions and FB’s social impact. Take a look.

Facebook in the news (video)

- Why You Should Be Worried About Facebook’s Metaverse – Vice, Dec 7, 2021

- Facebook executive blames users for believing misinformation – CNN, Dec 15, 2021

- How Facebook is Stealing Billions of Views – Kurzgesagt – In a Nutshell, Nov 10, 2015

Facebook in the news (print)

- Sarah Silverman Sues OpenAI and Meta Over Copyright Infringement – New York Times, July 10, 2023

- Meta Platforms Begins Blocking News for Canadian Users – Wall Street Journal, August 1, 2023

- Facebook Gave Police Their Private Data. Now This Duo Face Abortion Charges – The Guardian, August 10, 2022

- Facebook paid GOP firm to malign TikTok – Washington Post, March 30, 2022

- Buying Influence: How China Manipulates Facebook and Twitter – New York Times, Dec 20, 2021

- The Facebook Papers: What you need to know about the trove of insider documents -NPR, Oct 25, 2021

- Facebook Has Been Showing Military Gear Ads Next To Insurrection Posts – Buzzfeed News, Jan 13, 2021

- Researchers explain why they believe Facebook mishandles political ads – NPR, Dec 9, 2021

- Facebook did little to moderate posts in the world’s most violent countries – Politico, Oct 25, 2021

- Nearly 50,000 Facebook users may have been targets of private surveillance, company says – Washington Post, Dec 17, 2021

- A Facebook antitrust suit can move forward, a judge says, in a win for the F.T.C. -The New York Times.

Facebook and monopoly

- Blind spot: The attention economy and the law T Wu – Antitrust Law Journal, 2017

- The old media business in the new:’The Googlization of everything’as the capitalization of digital consumption B Nixon – Media, Culture & Society, 2016

Facebook and misinformation

- Misinformation spreading on Facebook F Zollo, W Quattrociocchi – Complex spreading phenomena in social …, 2018

- Trends in the diffusion of misinformation on social media H Allcott, M Gentzkow, C Yu – Research & Politics, 2019

- Dysfunctional information sharing on WhatsApp and Facebook: The role of political talk, cross-cutting exposure and social corrections P Rossini, J Stromer-Galley, EA Baptista… – New Media & Society 2020

- The Misinformation Society V Pickard – Antidemocracy in America, 2019

- Mapping misinformation in the coronavirus outbreak A Santos Rutschman – Health Affairs Blog, 2020

Facebook and addictive behavior

- Ethics of the attention economy: The problem of social media addiction VR Bhargava, M Velasquez – Business Ethics Quarterly, 2021

- The impact of Facebook addiction and self-esteem on students’ academic performance: A multi-group analysis AH Busalim, M Masrom, WNBW Zakaria – Computers & Education, 2019

- Social networking and academic performance: A review T Doleck, S Lajoie – Education and Information Technologies, 2018

- 61% of studies showed negative significant effects of social media use on students’ academic performance . . . only 4% reported a positive effect.

Facebook and self-esteem

- Negative social comparison on Facebook and depressive symptoms: Rumination as a mechanism. Feinstein, B. A., Hershenberg, R., Bhatia, V., Latack, J. A., Meuwly, N., & Davila, J. (2013). Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 2(3), 161

- “. . . negatively comparing oneself with others may place individuals at risk for rumination and, in turn, depressive symptoms.

- ”Envy on Facebook: a hidden threat to users’ life satisfaction? H Krasnova, H Wenninger, T Widjaja, P Buxmann – 2013

Facebook Critic Organizations

Capitol riots and the mythic memory of 1776

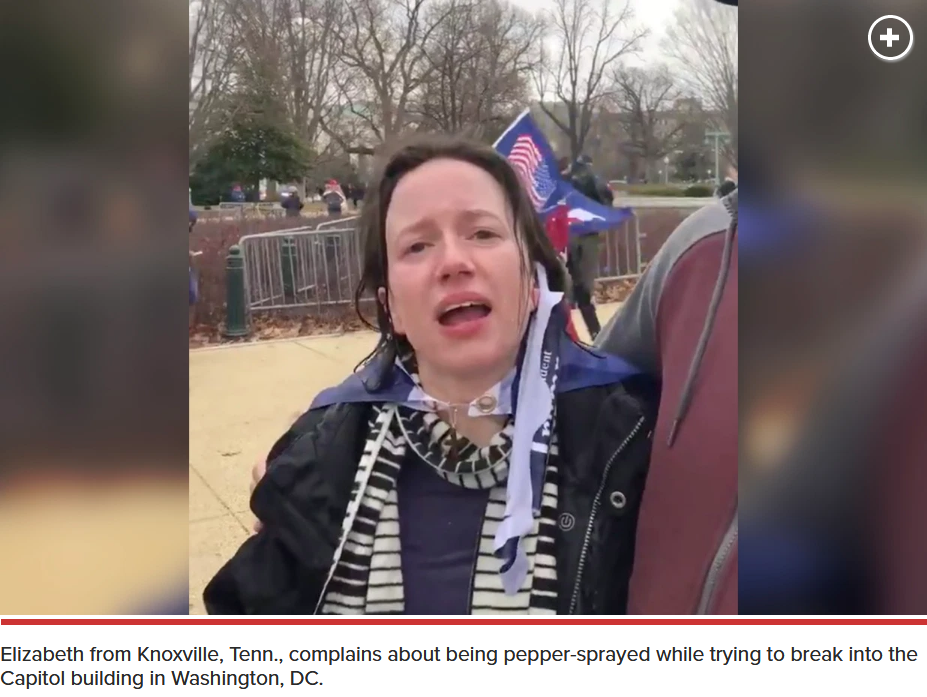

Interviewer: Ma’am, what happened to you?

Rioter from Knoxville: I got maced [wipes away tears, breathlessly]

Interviewer: You got maced. And what happened? You were trying to go inside the Capitol?

Rioter from Knoxville: [Indignantly] Yeah! I made it like a foot inside and they pushed me out and the maced me!

Interviewer: What is your name and where are you from?

Rioter from Knoxville: My name is Elizabeth; I’m from Knoxville, Tennessee!

Interviewer: And why did you want to go in?

Rioter from Knoxville: We’re storming the Capitol! It’s a revolution!

_______________

Attendees of Trump’s rally-turned-riot stormed the Capitol at the direction of the president. They attempted to stop Congressional certification of Joe Biden’s electoral win and the peaceful transition of power that has defined American government for centuries. But many rioters seemed unprepared considering the scale of their ambitions. The apparent surprise of the rioter from Knoxville at law enforcement’s response suggests many involved were animated by visions of revolution different from that of their flak-jacketed comrades. For rioters like Elizabeth, January 6th was a genteel, candy-coated revolution, closer to carnival than coup. She and others were Revolution Tourists.

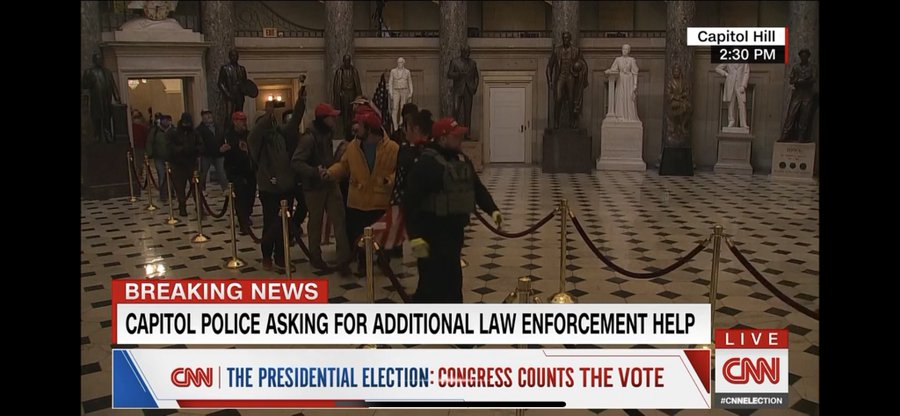

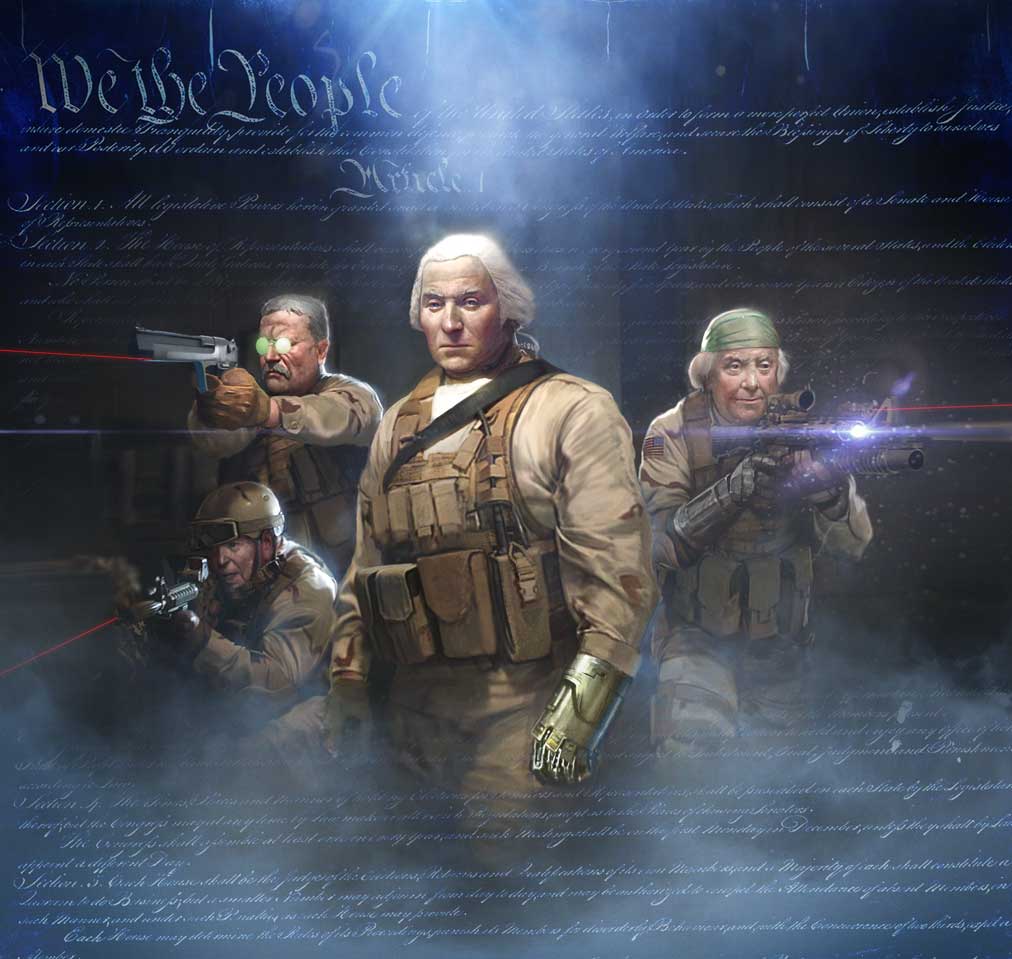

To be sure, many Capitol rioters were prepared for violence. Video footage shows the Capitol steps packed with men “kitted up” in tactical gear. They came in flak jackets, clutched zip-tie hand restraints and assault fashion reminiscent of Call of Duty. White men between 18 and 50 can be seen kicking doors down, busting windows and beating a fallen Capitol police officer because they believe conspiracies of election fraud promoted by Republican political leaders and far-right media.

Others storming the building, by contrast, seemed more prepared for festivities than ferocity. Live scenes at the Capitol had a jamboree atmosphere of Revolution Tourism. Amused and casually dressed middle-aged men took selfies with fellow rioters and Capitol officers. In plumes of tear gas, a well-dressed woman carefully lifts her stylish purse through a shattered window frame. A group of twenty-somethings scurried up and down climbing ropes like outdoor enthusiasts on a sporty weekend getaway. Once inside the building, many who had forcibly entered the broken doors of the building then formed orderly lines as they meandered through Statuary Hall within the velvet roped walkway.

These Tourist Revolutionaries were not dressed for violent insurrection. Nor were they happy patriots there to admire institutions of democracy, as Republican apologists have suggested. They were dressed for a Trump rally, and it is not clear that these festival-goers fully understood the gravity of their choices on that day. This does not make them less culpable. It does, however, make their actions more frightening. Elizabeth from Knoxville’s view of revolution speaks to the privilege and ignorance underlying the danger of a shallow and mythical version of the American Revolution and American politics in general.

Elizabeth became a meme after complaining to a reporter that she was maced when trying to break into the Capitol complex. The preposterousness of a “revolutionary” expressing indignation after being repulsed triggered the usual mockery online. Georgia Aspinall at Grazia has cautioned against such mockery. “The sheer delusion of this woman, so bold in her conviction that this was necessary, so confused and upset that police stopped her from attacking the US democracy . . . is terrifying.”

Aspinall is right. Beneath the easily mocked sense of entitlement is a deeply confused sense of American history and politics. Yes, the premise of election fraud that animated these crowds in the first place was a lie. The more pressing issue Aspinall sees is how Elizabeth from Knoxville was unable to recognize the difference between democratic and anti-democratic political action.

What should we make of the throngs who were not participating in a sort of serious-minded coup attempt like their flak-jacketed comrades? The insurrectionists in piano scarves and colorful tailgate facepaint suggest that these tourist revolutionaries saw the trip to DC (from New Jersey, Knoxville, Arkansas) as a symbolic performance of American independence and a rejection of elites cartoonishly painted for them by reckless political rhetoric and a post-Truth media ecosystem that greedily amplifies that which inflames.

The misunderstanding of American history that animated rioters is at the root of the conflict. Tourist Revolutionaries, energized by the symbolism of “1776,” confuse the tyranny of the monarch King George with the compromises of democracy and shared self-governance with fellow Americans. The carnival sense of patriotic revolt allowed rioters to happily pose for photos in the act of theft without a sense of the criminality of stealing. The carnival version of 1776 paints revolution as revelry and confuses protest with sedition.

If Elizabeth from Knoxville’s shock is genuine, it suggests that many of the rioters cannot understand that they have broken laws. In their minds, they should have the privilege to trespass because the Capitol is public property, their property. Elizabeth may have wondered how patriots could be on the wrong side of the law.

Rioters like Elizabeth have a mythical and sanitized understanding of American history, one that has lost the gritty and horrifying elements of revolution. The amputated limbs. The slumped bodies after British soldiers fired into an angry Boston crowd. The newspaper editors who were jailed for insulting colonial governors. The tyranny of princely rule without representation. These dirty and gangrenous parts of the American Revolution are missing from Elizabeth’s version of American history. As a tourist, Elizabeth understood threatening lawmakers as an extension of patriotic citizenship.

Tourist Revolutionaries on display during the Trump riot were engaging in a symbolic act that reenacts a mythical history of the country. Like visitors to a Renaissance fair or audiences at Medieval Times Dinner Theater, they did not expect authorities to respond to illegal occupation of Federal buildings with force. Her indignation speaks volumes about how symbols of political rhetoric can obscure the very real danger of “doing revolution.” Being met with force is surprising to those participating in Tourism Revolution. They complain of injury as if slapped by Goofy at Disneyland.

This was a symbolic act for a substantial number of Trump supporters who were misled by President Trump to believe they were fighting for the preservation of America rather than the subversion of electoral democracy to prop up the president’s personal ambitions.

Tourist Revolution performs a celebratory but incomplete understanding of American history, one all Americans share at Fourth of July parties and fireworks displays standing in for the red glare of actual warfare. The symbolic rhetoric that brought Elizabeth and others to the nation’s capital became literal, but it is not clear that many rioters understood the difference. This should come as no surprise in a political-media system unable to sort myth and symbol from reality for citizens. As these symbols slip from protest speech to seditious action, we can see that our fractured media is not just a quirk of social media. It is a threat to democratic governance more menacing than any pitchfork or pipebomb.

An American politics of symbols, or the triumph of “symbolitics”

“Climate skepticism has become a tenet of populism — a revolt against elitist scientists and liberal politicians seeking excuses for social and economic control. The denial of climate change has become a cultural signifier, the policy equivalent of a gun rack in a truck.”

-Washington Post opinion columnist

“When [Trump] makes claims . . . the press takes him literally, but not seriously; his supporters take him seriously, but not literally.”

–The Atlantic, September, 2016

“I think a lot of voters who vote for Trump take Trump seriously but not literally, so when they hear things like the Muslim comment or the wall comment, their question is not, ‘Are you going to build a wall like the Great Wall of China?’ . . . What they hear is we’re going to have a saner, more sensible immigration policy.”

-Paypal co-founder and Trump supporter, Peter Thiel

Political polarization has shifted how Americans self-identify, and much of this recent transformation stems from symbolic forms of civic engagement. The political animosity that has a stranglehold on politics – harbingers of civil war for a worried few – suggests Americans are increasingly reliant on politics of symbols to frame our personal identities and interpret power in 21st century American life.

This is frustrating for journalists who wring their hands over “fact-free” discourse or new media misinformation. And it’s understandable given journalism is ostensibly a fact-based profession. But the mainstream press may have a problem of being naively literal in an increasingly symbolic political world.

Much of the journalistic marveling, some quite condescending, is in response to Trump’s voter base. To understand the disconnect between professional journalists and Trump’s base, we should recognize how a marriage of entertainment and political culture fueled his political rise. Television fandoms from the entertainment culture -The Apprentice, World Wrestling Entertainment- took the small step into the public sphere. As Trump’s familiar face from entertainment media moved into political media, the 2016 campaign drew on that television audience.

But it did more than draw voters. It also imported the logics of reality TV. Ratings took on heightened importance. Crowd size became worthy of debate. The political theater took on the carnival atmosphere of a wrestling arena in which voters could organize around the symbols of heroism and villainy. Entertainment culture colonized the political realm and imported the energy and emotion of reality TV.

Part of the entertainment-politics melding is a fuller shift of political reasoning from a messy world of policy details to a clean and easily understood world of symbolic narratives in which moral assertion displaces analytic nuance. The preference for the digestible world of symbols over factual debate precedes Trump but reached new proportions with his presidency and will likely continue beyond it.

It might be wise to more fully recognize how American politics has become a game of cultural signifiers. And yet, elite newsrooms are unable to recognize the symbolic language of American citizenry. For many, American politics is a game of bipolar brinkmanship dealing in mythic symbols that funnel debate into an either/or dynamic of the two-party system.

We can hear it in casual conversations among the politically like-minded: “I could never date a Republican.” Or in how we regard politically mixed marriage: “I wonder what it is like at THAT dinner table!” In modern America, fathers are more likely to object to daughters bringing home the political opposition than a love interest of a different race. As Iyengar and Westwood put it, “party cues exert powerful effects on nonpolitical judgments and behaviors.” A politics-first identity has subsumed other social roles, and we can see it in reports of estranged family members and politically severed friendships.

Viewing political orientation as a deal-breaker in our romantic lives and wondering at “political miscegenation” underscore how partisan identities have taken a more central role in our broader social lives. Though the democratic ideal says we “should” vote according to tangible identities of self-interest (a small business owner or cancer survivor or blue-collar worker) we increasingly rely on artificially binary identities crafted by a symbol systems of commercial media and political elites.

Today, we are less likely to participate in politics as ourselves. Instead, we participate as “real Republicans” or “true progressives.” We act as representatives of packaged ideologies rather than individuals directly voting for a better life through self-governance. I suspect the “symbolification” of political culture is both a symptom and a cause in this process.

Reporting QAnon: a symbolic politics

What are the consequences when American politics, already prone to partisan theater, embraces an affective world of symbolism? To what degree do polarized cultural identities in the political realm necessitate the conversion of policy battles into symbols or battles over mere symbols?

These are ponderous questions, but I can map out some potential fallout.

First, the increasing power of symbolic communication in high politics has consequences for traditional understandings of democratic politics that are built into professional news frames.

Symbolification distances public debate from the actual machinery of government. Instead of addressing the confusing details of healthcare or the tax system, symbols stand in with broad caricatures of the issue and the political agents that represent them. Symbolic politics offers a cast of evil-doers and heroic figures fighting for politically vague but symbolically meaningful goals.

The degree to which policy debates devolve into symbolic representation is a fair approximation of the degree to which citizens directly control their government. A shallow symbolic system can replace details of party platforms or voting records. As a result, citizen judgement is one step removed.

Second, importing the symbols of entertainment culture may exacerbate partisan divisions. As differing symbolic systems ensconce and separate American subcultures, unifying themes of nationality weaken. Participation in politics through symbolic representations allows the public to address very different worlds with little hope of solving the very real social problems facing the nation. A common creed that has historically shored up American identity fragments along the fault lines of confirmation biases. The symbolic center cannot hold.

Finally, the reliance on symbols to navigate American politics plays into the vagaries and smoky mysticism of conspiracy mongers. Why would an American raise doubts about the American moon landing? Taken literally, the claim is absurd. Taken symbolically, it captures a broad suspicion that government is deceitful and so power-hungry that it would orchestrate a grand public deception to achieve “its” goals. The specific theory that the moon landing was faked does not itself need to be true as a symbolic representation of a calloused, elite government manipulating the public. The conspiracy is “true” even if Lance and Buzz actually took that one small step.

This is why literary semiotics may be a better tool for understanding American politics than political science or a burst of polls calculated, correlated, crunched and recrunched. The role of symbols in movements inspired by QAnon illustrates how current tools of of professional journalism produce blindspots in political analysis.

QAnon: reading conspiracies as semiotic politics

“. . . conspiracy theory [is[ an entertaining narrative form, a populist expression of a democratic culture, that circulates deep skepticism about the truth of the current political order throughout contemporary culture.” (Fenster 1999, pg. xiii).

Politics is rather boring in the details. That’s why C-Span is not a ratings hit. Watching senators argue policy in front of an empty chamber is mind-numbing and, frankly, uninformative for anyone but DC insiders or beat reporters.

By contrast, online corners of conspiratorial thought like QAnon give gripping narrative structure to the sense of powerlessness in modern America. From the electoral college to tax policy, American democracy has features that are glaringly elite. QAnon merely gives a narrative to a fundamental truth felt by many Americans: powerlessness.

What is QAnon? The group is known for its wildest assertion that a cabal of Satan-worshipping elites control key government and media operations. This secret organization is engaged in child sex crimes at a massive scale. In some versions, these elites consume children’s blood to extend life or otherwise sustain themselves.

QAnon researchers have found no coherent, single narrative that defines the movement. Under the umbrella of QAnon, there are factions who have “different ideas about who the cabal is and what their ultimate goals are . . . but they are united in the belief that everything is a lie and the order needs to be destroyed.” It is more a patchwork of unorthodox explanations of power in America.

Taken literally, the conspiracy movement fails tests of evidence required by professional journalists as well as classrooms and the courts. If we de-emphasize the narrative specifics and read these beliefs as metaphor (don’t take it literally but take it seriously), the basic structure of the theory is true. As metaphor, the narrative is a archetypal story of the powerful preying on the weak.

In fact, wealth gaps and power divisions do define modern America. Two-thirds of U.S. senators’ net worth exceeds $1 million. As Pew researchers note, income growth in recent decades has tilted to upper-income households and the middle class has shrunk. Nearly three-quarters of all employees live paycheck-to-paycheck in 2020. The popular vote often fails to elect presidents, defying the public will for arcane legalistic reasons. Given these conditions, the myth created by “Q” can make sense emotionally even if it fails intellectually.

We can understand the more outrageous conspiracy theories as a consequence of America’s crippled ability to recognize class conflict. If a group of people don’t have a language of class-based oppression -e.g. “haves and have nots”- they turn to alternative explanations for the inequality they feel. Pedophilia stands in as a morally charged symbol for victimization.

On the other side of this growing economic disparity, the investor class buys and sells holdings according to the logic of financial capital. If their children don’t earn admission to prestigious schools, the elite bribe their way into East and West coast schools.

This is why QAnon functions a redemption narrative comparable to Christian religious movements. It involves faith in something deeper than facts show us and belief without clear evidence. However far-fetched, conspiracy paints a symbolic picture that explains the sense of powerlessness felt by many.

At once, “Q” offers a way to resist that oppressive force. It provides comfort by painting a world of stark good and evil in which clear heroes work to save the faithful and punish the villainous. Adherents decode and scrutinize the meaning of Q’s pronouncements like ecclesiastical priests engaged in Biblical hermeneutics. Retweeting Q or interpreting Q’s “drops” becomes an act of defiance by speaking truth to nefarious but poorly understood power in America. The congregants evangelistically hope to reveal the truth to nonbelievers and instigate a “great awakening.”

A symbolic analysis of culture might produce more useful maps for navigating this strain of American politics, and it certainly reveals more than the quantitative approach taken by poll-obsessed news networks that treat elections like horse-races. As symbolism displaces more direct citizen engagement with matters of government, the assumptions of political journalism become less reflective of actual political processes and opinion formation in American life.

The growing wedge between mainstream news and parts of the American public stems from these divergent epistemologies. Traditional journalism functions as a gatekeeper, filtering the non-factual out of public discourse. The growing part of the American public who engage with politics though symbolic narratives see this realist epistemology as censorship and oppression. News perpetuates a fiction that numbers are an accurate representation of reality. Journalists, true to their professional training, dismiss counterfactual political thoughts with a myopic literalism.

But the political class only shoots itself in the foot when it dismisses symbolic discourse. New York Times columnist, David Brooks, argues that “personal contact” is the way to “[reduce] the social chasm between the members of the epistemic regime and those who feel so alienated from it.” Journalists may not be able to personally reach out to the alienated, but newsrooms can certainly pay greater attention to the symbolic dimensions of political culture and better understand the reality buried in the myths that shape the “paranoid style” of American politics.

Symbols have and will always play a role in political movements. Just look at the flags arrayed during the Capitol riots. It is uncertain, however, if 21st century journalism can develop analysis that both maintains fact-based discourse and productively accounts for the emerging centrality of symbols in political life. But a wholesale shift to symbolic public discourse threatens to unmoor democratic participation from meaningful self-governance.

Amusing Ourselves to Death: the Mueller report, TV hearings and Neil Postman

“It’s the Superbowl of things on C-SPAN at Eight-thirty in the morning.”

-Stephen Colbert

Robert Mueller and media critic Neil Postman have something in common. They are skeptical of television. Truth, for Postman, was fundamentally shaped by the medium of expression. In the old-timey age of print (i.e., Lincoln-Douglas debates), Americans thought in longer, more contemplative ways. How a society debates what is true and right, Postman claimed, is fundamentally shaped by the dominant medium of the time.

Under TV, our access to truth passes through a technicolored prism. Postman was concerned that we would lose the kind of thinking that made democracy work. TV’s flurry of sound bites and images threatened to shallow the American mind. Mueller’s testimony shows the special counsel’s own Postmanesque preference for the printed word as a means to determining truth.

What we call “watching television” is supposedly on the way out. TV viewing has declined by 3 to 4% per year since 2012, according to the Reuters Institute at Oxford. At once, our use of online video has increased dramatically. This begs the question: Have we stopped watching or do we simply access TV in different ways?

Of course, how we watch TV has changed considerably since Postman wrote Amusing Ourselves to Death in the 1980s. TV beams from smaller screens. It’s more individual. We watch it in office jobs, on the train and on demand. But the basic practice of “watching TV” remains unchanged. We still rely on sound bites, rapid images and visual narratives to understand the world. In many ways, TV just got small enough to come with us when we left the house.

TV in the 1980s shares at least one feature of its more mobile version today. TV always prefers to trade in spectacle. A medium focused on satisfying visual needs of passive audiences relies on spectacle. The problem for Postman and his bookish devotees is that spectacle only gets at certain truths: those that can be abbreviated and visually dramatized. Postman feared that the transition to a televisual society meant making everything “silly.” The loss of print culture, he reasoned, meant losing access to the forms of truth only available through the deliberation of reading and writing.

Which brings us back to Mueller.

The Special Cousel’s testimony revealed more about his faith in reading than the misdeeds of the president. Channeling the grumpy spirit of Postman, the Special Counsel refused to even read aloud from his own report as if the truth of the report could only reside in the printed word. Mueller referred committee members to the written work of the Special Council’s office at least 20 times. He welcomes the public to read the report, but he would not willingly act it out for television audiences.

Mueller’s stonewalling was frustratingly beautiful. He knew he was being displayed to an American audience. Predictably, partisans would try to coax out a visually anchored statement about Trump’s guilt or innocence.

He was painfully aware that his questioners, particularly Democrats, wanted to move the information in the 400+ page print report to modern American television, from inert and colorless words on a page to more vivid descriptions directly from the investigators face.

Clearly the former FBI head is trained to avoid partisan warfare and would not “perform” the report for a 24-Hour news channel industry. But, Mueller’s preference for the written version of his report ran counter to the hope members of the House had for his appearance.

These attempts to spread the Mueller Report from print-based audience to television-based audience indicate how much influence the political class believes TV to possess. The plan seemed to be to televise the report targeted a non-reading public with the hope that reproducing the same information in a visual format would reanimate public discourse and foster public discussions that undermine Trump’s support among swing voters.

Camera ready Republicans and Democrats were trying to enlist television’s storytelling power. They wanted something concisely stated before a camera. They want punch. They want the six-second sound bite. Mueller knows this, and you can hear it in every reluctant stutter of his testimony. The printed word should speak for itself.

Democrats needed to sway non-reading, politically active swing voters that have a reasonable likelihood of either voting Democrat or staying at home on election day. But the strategy also relied on a camera-friendly hearing that animated the sins of the presidency. For better or worse, Mueller’s print bias did not allow politicians to use the abbreviating power of TV.

It remains to be seen if print can still capture the American imagination or if Postman was right and the American public, atrophied by decades of spectacle politics, believes only what it sees.